The Role of the Median Nerve in Hand Function

Origin and Course

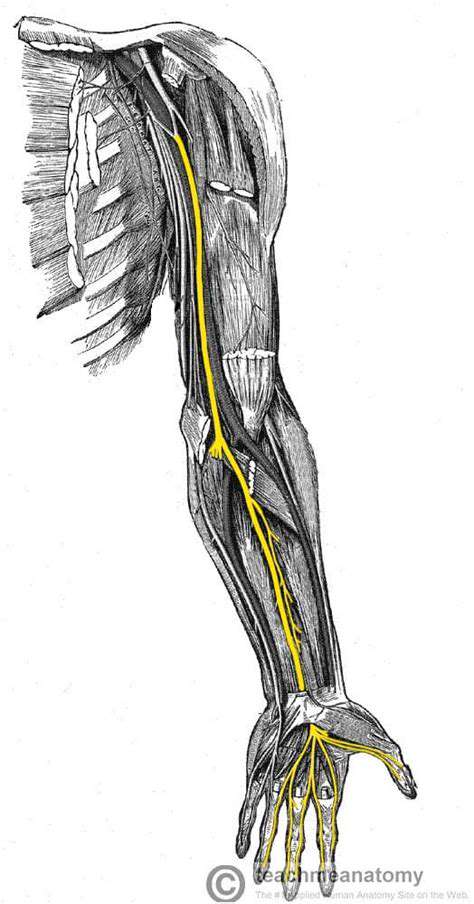

The median nerve emerges from the brachial plexus, specifically from the medial and lateral cords formed by spinal nerves C5 through T1. This intricate neural highway weaves through the upper limb, starting in the axilla and coursing down the arm's anterior compartment before reaching its final destination in the hand. This precise anatomical journey explains why even minor disruptions can significantly impact hand function. The nerve's path through tight anatomical spaces makes it particularly vulnerable to compression.

Sensory Distribution

This critical nerve provides feeling to the thumb, index finger, middle finger, and the radial side of the ring finger - essentially the lateral three and a half digits. Both palm and dorsal surfaces of these areas rely on median nerve input. Clinicians must memorize this sensory map, as it's the key to identifying median nerve pathology. The nerve also carries sensation from specific forearm regions, creating a comprehensive sensory network essential for fine motor control.

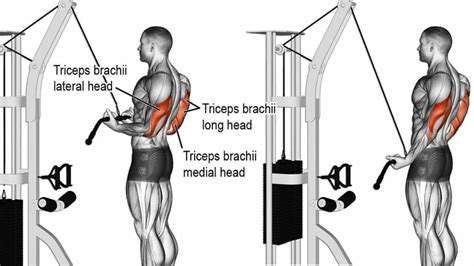

Motor Distribution

The median nerve powers numerous forearm and hand muscles, including the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor pollicis longus. Without proper median nerve function, simple acts like buttoning a shirt or holding a pen become impossible. These muscles enable the precision grips and delicate manipulations that define human dexterity. The nerve's motor contributions explain why median nerve injuries can be so debilitating in daily life.

Anatomical Relationships

The median nerve travels in close company with the brachial artery and vein through the arm's anterior compartment. This intimate vascular relationship means trauma to one structure often affects the others. Surgeons must navigate these anatomical neighbors carefully during procedures. The nerve's position also explains why certain fractures or swellings can compromise its function through compression.

Clinical Significance

Carpal tunnel syndrome represents just one of many conditions affecting median nerve function. Patients typically report nighttime hand numbness, weakened grip, and tingling in characteristic finger distributions. Early recognition of these symptoms prevents permanent nerve damage. Other median nerve pathologies include pronator syndrome and anterior interosseous nerve syndrome, each with distinct clinical presentations.

Branches and Divisions

As the median nerve descends, it gives off several important branches. The anterior interosseous nerve and palmar cutaneous branch serve specific regions before the main trunk enters the hand. These anatomical subdivisions explain why some median nerve injuries spare certain functions while affecting others. Precise knowledge of these branches helps clinicians localize lesions with remarkable accuracy.

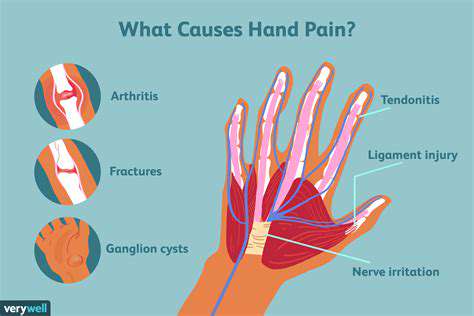

Potential Injuries and Damage

Median nerve injuries range from temporary compression to complete transection. Common mechanisms include wrist lacerations, forearm fractures, and prolonged pressure. The resulting symptoms - numbness, weakness, and characteristic hand postures - form the basis of clinical diagnosis. Timely intervention often determines whether patients regain full function or develop permanent deficits. Preventative strategies focus on ergonomic modifications and early symptom recognition.

Sensory Contributions of the Median Nerve: Feeling the World

Visual Impact of Media

Modern media relies heavily on visual elements to convey information and emotion. Well-designed visuals communicate complex ideas more effectively than text alone, engaging multiple brain regions simultaneously. Color psychology influences viewer perception, with warm hues often evoking different responses than cool tones. Composition and lighting direct attention and establish mood, making visual media a powerful tool for storytelling and education.

Auditory Engagement in Media

Sound design transforms visual media into immersive experiences. Strategic use of music can elevate heart rates during action sequences or induce calm in reflective moments. The human brain processes auditory information faster than visual input, making sound crucial for immediate emotional impact. Dialogue clarity, ambient noise, and sound effects all contribute to perceived realism and engagement.

Tactile Sensations and Media

While direct tactile feedback remains limited in traditional media, innovative technologies are bridging this gap. Virtual reality systems now incorporate haptic feedback to simulate texture and resistance. These tactile cues enhance immersion and learning retention significantly. Even without physical touch, skilled media creators can evoke tactile sensations through careful visual and auditory cues.

Olfactory Experiences in Media

Smell remains the most challenging sense to replicate in media, yet it's powerfully evocative. Clever media producers use visual and auditory cues to trigger olfactory memories. The mere mention of specific scents can transport audiences to different times and places. Emerging technologies like scent-emitting devices may soon expand media's olfactory dimension, particularly in therapeutic and educational applications.

Gustatory Sensations in Media

Food media demonstrates taste's powerful role in engagement. Close-up shots of sizzling dishes, crisp sound effects, and vivid descriptions activate the brain's gustatory centers. This neural mirroring explains why food programming often triggers actual hunger responses. Culinary content creators master these multisensory techniques to maximize viewer engagement and retention.

Multisensory Integration in Media

The most impactful media experiences synchronize multiple sensory channels. When visual, auditory, and other sensory elements align perfectly, they create unforgettable moments that resonate emotionally and cognitively. This integration explains why certain media pieces become cultural touchstones while others fade quickly. Understanding sensory integration helps creators develop more effective educational and entertainment content.

Clinical Significance: Recognizing Median Nerve Dysfunction

Understanding Median Nerve Anatomy

The median nerve's complex anatomy explains its clinical importance. Emerging from the brachial plexus, it navigates several potential compression points before terminating in the hand. Key anatomical landmarks like the carpal tunnel and pronator teres muscle represent critical diagnostic checkpoints. Clinicians must visualize this three-dimensional pathway to accurately assess dysfunction.

Clinical Presentation of Median Nerve Dysfunction

Median nerve disorders manifest through characteristic symptom patterns. Patients typically report numbness in specific fingers, weakened pinch grip, and sometimes visible thenar muscle wasting. The timing and progression of symptoms often reveal the underlying etiology. Careful history-taking differentiates acute trauma from chronic compression syndromes.

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: A Common Culprit

As the most frequent compressive neuropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome affects millions worldwide. Repetitive hand use, metabolic conditions, and anatomical variations all contribute to its development. Nocturnal symptoms and positive Phalen's test help distinguish CTS from other neuropathies. Early intervention with splinting or steroid injections often prevents surgical intervention.

Pronator Teres Syndrome: A Less Frequent Cause

This less common compression neuropathy occurs where the median nerve passes between the pronator teres muscle heads. Unlike CTS, symptoms typically involve forearm pain and worsen with repetitive pronation. Careful physical examination must differentiate it from more proximal nerve lesions. Treatment often combines activity modification with targeted physical therapy.

Differential Diagnosis and Diagnostic Procedures

Accurate diagnosis requires methodical evaluation. Nerve conduction studies measure signal velocity across potential compression sites, while EMG assesses muscle response. These objective tests complement physical examination findings to localize lesions precisely. Additional imaging may be necessary for space-occupying lesions or traumatic injuries.

Management and Treatment Strategies

Treatment ranges from conservative measures to surgical release, depending on severity. Early-stage compression often responds well to activity modification and night splinting. Surgical candidates require careful preoperative counseling about expected outcomes and rehabilitation timelines. Postoperative therapy focuses on restoring strength while preventing scar tissue formation.

Read more about The Role of the Median Nerve in Hand Function

Hot Recommendations

- The Impact of the Digital Age on Hand Function

- The Role of Hands in Agricultural Innovation

- The Impact of Technology on Hand Artistry

- The Importance of Hand Care for Artists

- How Hand Control Enhances Robotic Surgery

- The Impact of Hand Strength on Physical Labor

- How Handwriting Influences Cognitive Development

- The Impact of Environmental Factors on Hand Health

- The Power of Hands in Building Community

- The Importance of Ergonomics in Hand Health