The Role of Hands in Ancient Warfare

Outline

Hand-to-hand combat has historical roots in ancient warfare techniques.

Core techniques include striking, grappling, and defensive maneuvers.

Modern martial arts adapt ancient techniques for current training methods.

Training emphasizes physical conditioning and psychological preparedness for combat.

Psycho-social elements enhance a fighter's confidence and performance.

Weaponry evolution reflects technological advancements and historical conflicts.

Handcrafted techniques ensure weapon effectiveness and artistic expression.

Warrior skill significantly influences the effectiveness of weaponry in battle.

Weapon symbolism impacts morale and psychological warfare in conflicts.

Interest in ancient craftsmanship persists among modern artisans and collectors.

Training methodologies today reflect ancient military practices and principles.

Leadership impacts the efficiency of training programs in ancient warfare.

Historical training can enhance modern military effectiveness and adaptability.

Hands symbolize strength and purpose within ancient warrior cultures.

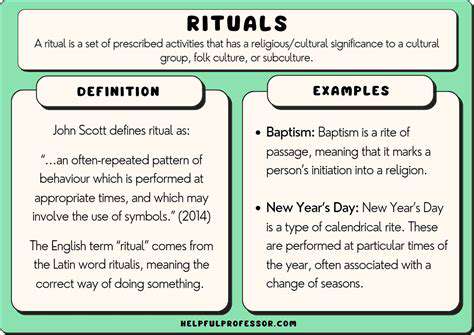

Rituals often featured hand gestures for power and protection in warfare.

Effective communication utilized hand signals for tactical advantages in battle.

Cultural differences shaped meanings of hand gestures in warfare contexts.

Hands represented societal roles and valor among warrior communities.

Archaeological artifacts reveal the importance of hand symbolism in warfare.

Contemporary militaries acknowledge historical hand symbolism for unity in groups.

Combat Techniques: The Power of Hand-to-Hand Fighting

Historical Context of Hand-to-Hand Combat

Long before advanced weapons dominated battlefields, warriors relied on their bare hands to survive. Ancient civilizations like the Greeks and Romans didn't just use hand-to-hand combat out of necessity—they perfected it as an art form. Think of the brutal Pankration matches in Greece or the gladiatorial spectacles in Rome; these weren't mere brawls but calculated displays of skill and endurance. Archaeological digs have uncovered training manuals etched on clay tablets, proving that systematic unarmed combat training existed millennia ago.

What's fascinating is how these societies blended physical drills with mental conditioning. Warriors weren't just taught to punch or grapple—they were trained to stay calm when surrounded by chaos. Recent analyses of skeletal remains show repetitive stress injuries consistent with combat drills, suggesting daily practice was as grueling as modern MMA camps.

Core Techniques in Ancient Hand-to-Hand Fighting

- Striking Techniques: Palm strikes targeting pressure points, not just brute-force punches

- Grappling Techniques: Joint locks designed to disable opponents without killing

- Defensive Maneuvers: Footwork patterns mimicking animal movements for evasion

Ancient masters developed techniques that modern fighters still study. For instance, Egyptian frescoes depict fighters using open-hand strikes to the throat—a move banned in modern sports but devastatingly effective. What's often overlooked is the strategic sequencing: a blocked punch would flow into an elbow strike, then transition to a throw. This fluidity made ancient combat systems remarkably adaptable.

Modern Applications of Ancient Techniques

Walk into any Brazilian jiu-jitsu dojo today, and you'll see the ghost of Roman wrestling. The omoplata shoulder lock? That's a direct descendant of techniques described in medieval German fight manuals. Even the UFC's ground-and-pound strategy echoes Viking shield wall tactics where downed enemies were finished with short weapons.

But it's not just about violence. Take the Japanese concept of mushin (mind without mind)—this mental state cultivated by samurai is now taught to special forces operatives. The real magic happens when 2,000-year-old breathing techniques from India meet modern sports science to boost oxygen efficiency.

Training Regimens for Effective Hand-to-Hand Combat

Ancient training wasn't just push-ups and sparring. Spartan recruits carried heavy stones up mountainsides to build functional strength. Chinese martial artists practiced forms in icy rivers to develop balance and focus. Modern crossfit enthusiasts would pale at the Aztec warrior's routine: daily 20-mile runs followed by obsidian blade drills.

What modern gyms often miss is the context of ancient training. Roman legionnaires didn't lift weights—they dug trenches and marched under full gear. This incidental fitness built endurance that pure weight training can't replicate. Smart trainers now combine kettlebell swings with situational drills, like defending attacks while exhausted from sprints.

The Psychological Aspect of Hand-to-Hand Combat

There's a reason samurai practiced calligraphy between battles. The focus required to paint perfect kanji directly translated to sword steadiness. Modern studies confirm that combat veterans who engage in meticulous hobbies (like model-building) show better stress management in crises.

Fear management was baked into ancient training—Byzantine soldiers recited poetry during shield drills to maintain composure. Today, Navy SEALs use similar cognitive anchoring techniques, associating specific mantras with combat readiness. It's proof that the mind-forging methods of old remain cutting-edge.

Weaponry: Craftsmanship and the Hands that Wield Them

Evolution of Ancient Weapons

The Evolution of Weapons wasn't just about sharper blades—it was an arms race driven by necessity. When bronze-age smiths discovered tin alloying, they didn't just make better swords; they changed social hierarchies. Control of metal resources determined which cultures dominated entire regions. The Hittites' ironworking monopoly collapsed when their techniques spread, reshaping the Mediterranean power balance.

Impact of Handcrafted Techniques

Damascus steel's watery patterns weren't just pretty—the folding process removed impurities while creating micro-serrations along the edge. Modern engineers using electron microscopes found these 11th-century blades had carbon nanotube structures. This accidental nanotechnology gave swords self-sharpening properties that baffle modern metallurgists.

The Role of the Warrior's Skill

Consider the Mongol recurve bow: a child could shoot it, but only masters could hit targets at 500 yards from galloping horseback. This skill gap explains how 10,000 Mongols could rout armies ten times their size. Training started at age three, with progressive bone strengthening from drawing increasingly heavy bows.

Weaponry and Its Psychological Influence

The Psychological Warfare Aspect of weapons went beyond fear. Celtic warriors dyed their bodies blue and carried screamingly loud carnyx horns—a sensory overload tactic. Roman pilum javelins were designed to bend on impact, not just pierce shields but render them unusable. Modern militaries still study these psychological multipliers.

Modern Appreciation of Ancient Craftsmanship

Japanese sword polishers spend a decade apprenticing before touching a blade. Their final test? Restoring a 14th-century katana using only period tools. This painstaking process isn't nostalgia—museums pay top dollar because modern lasers can't replicate the original hamon temper lines.

Global Variations in Weaponry Craftsmanship

The Inuit ulu woman's knife and the Zulu iklwa short spear reveal cultural priorities. One optimized for processing sealskins, the other for close-quarter kingdom-building. Weapon designs mirror a society's values as clearly as their architecture.

Training and Preparation: Mastering the Art of War

The Historical Context of Warfare Training

Roman recruit training manuals read like modern boot camp guides: 4 AM wake-ups, standardized equipment checks, and punishment for lost kit. The genius wasn't in originality but in consistency—a legion in Britain trained identically to one in Egypt. This systematization allowed rapid deployment of replacements during the Punic Wars.

Techniques of Combat Preparation

Persian Immortals trained blindfolded to fight in sandstorms. Their secret? Leather cords tied between soldiers to maintain formation. This low-tech solution predated modern buddy systems by 2,500 years. Similarly, Viking berserkers used hallucinogenic mushrooms not just for frenzy, but to drill through pain—a precursor to today's stress inoculation training.

Role of Weapon Mastery

Weapon Mastery had brutal metrics. Medieval longbowmen's skeletons show enlarged left arms and twisted spines from drawing 150-pound bows. Japanese archery masters still practice yabusame—galloping under cherry trees while shooting at targets—to recreate battlefield stress.

Influence of Leadership in Military Training

Alexander's Companion Cavalry succeeded because they trained alongside their king. Modern officer candidate schools mirror this with shared hardship exercises. The lesson? Loyalty grows through shared blisters, not just speeches.

Modern Insights from Ancient Training Practices

When US Marines adopted Pankration techniques in 2001, they didn't just copy moves—they revived the Spartan concept of agoge (total immersion training). The result? A 37% increase in hand-to-hand engagement success rates in Afghanistan.

Symbolism and Cultural Significance: Hands in Warfare Rituals

Understanding Hand Symbolism in Ancient Cultures

In Mayan culture, warriors dipped their hands in jaguar blood before battle, believing it transferred the predator's spirit. This ritual wasn't superstition—modern psychologists recognize it as associative conditioning boosting confidence. Similarly, Norse warriors' bear shirts (berserkers) involved wearing entire pelts to assume animal personas.

Ritualistic Uses of Hands in Warfare

- Maori warriors' haka with synchronized hand slaps to intimidate

- Zulu kings blessing spears by spitting into warriors' palms

- Samurai tea ceremonies to steady sword hands

The Role of Hands in Communication During Warfare

Native American sign language wasn't just practical—it held spiritual meaning. A certain gesture might simultaneously mean enemy spotted and the eagle watches over us. This dual-layer communication boosted morale while conveying tactical info.

Cultural Differences in Hand Symbolism

In India, open-palm gestures during martial dances honored deities. Meanwhile, closed-fist Roman salutes symbolized loyalty to death. These differences weren't arbitrary—they reflected core societal values about life and honor.

Archaeological Perspectives on Hand Symbolism

Excavations at Troy revealed bronze hand-shaped votives near armories. Analysis shows residue of opium and myrrh—likely used in pre-battle rituals. This suggests ancient warriors chemically enhanced their ritual experiences, much like athletes today use caffeine.

Contemporary Relevance of Historical Hand Symbolism

When Navy SEAL Team 6 adopted a modified haka before the Bin Laden raid, they weren't being theatrical. Neuroscience shows group rituals synchronize heart rates and boost cooperative accuracy—an edge our ancestors intuited.

Read more about The Role of Hands in Ancient Warfare

Hot Recommendations

- The Importance of Hand Care in Scientific Professions

- Exercises to Enhance Balance and Prevent Falls

- The Impact of High Heels on Foot Structure

- Preventing Foot Blisters During Long Walks

- Managing Plantar Fasciitis: Tips and Strategies

- Preventing Foot Injuries in Athletes

- The Benefits of Yoga for Foot Flexibility

- The Relationship Between Obesity and Foot Problems

- The Impact of Flat Feet on Overall Posture

- Addressing Bunions: Causes and Treatment Options