The History of Sign Language and Its Development

Early Forms of Communication

Long before words shaped our interactions, humans relied on silent dialogues. Faces spoke volumes without uttering sounds, hands painted stories in the air, and bodies danced with unspoken meanings. These primal conversations built the first bridges between minds, creating bonds that held tribes together against nature's challenges. When danger lurked or food was found, these wordless warnings meant survival.

Our ancient ancestors filled the air with rough sounds - grunts that carried joy, hoots that signaled alarm, growls that marked territory. While crude by today's standards, these vocal sparks ignited humanity's linguistic fire. Studying these beginnings reveals how grunts gradually gained grammar, transforming into the rich tapestry of human speech.

Rudimentary Symbolism and Pictographs

As communities grew, so did the need for messages that could outlast their makers. Early innovators began etching stories into stone, painting memories on cave walls. These first hard drives stored knowledge across generations, letting wisdom travel through time. A simple drawing of a bison could warn of danger or promise food, carrying meaning far beyond its lines.

This visual revolution changed everything. Suddenly, knowledge didn't die with its keeper. Stories could sleep in stone until future eyes awakened them. Cultures began building shared memories, creating identities that stretched beyond single lifetimes.

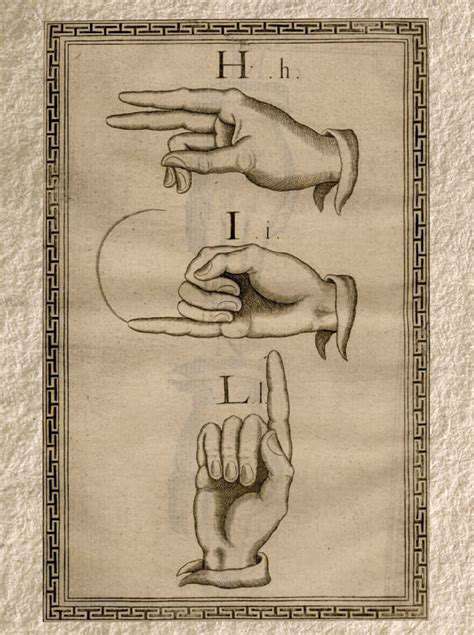

The Development of Gestural Languages

While most think of speech when imagining language, hands have been speaking eloquently for millennia. Where sound failed, gesture flourished, creating complete linguistic worlds in the air. Deaf communities didn't just adapt existing languages - they built entirely new ones from movement and expression, proving communication needs no sound to be rich and complex.

Pre-linguistic Vocalizations

Before sentences existed, emotion ruled the voice. A mother's comforting hum, a hunter's warning cry - these raw sounds carried meaning long before words defined them. Scientists studying these vocal fossils uncover how emotion gradually gained structure, how instinctive sounds slowly shaped themselves into language's building blocks.

Early Forms of Storytelling

Around ancient fires, humanity's first teachers didn't lecture - they performed. Through dramatic reenactments, rhythmic chants, and exaggerated gestures, elders encoded survival lessons in memorable packages. These living libraries carried entire cultures in their performances, ensuring that even without writing, knowledge could journey safely into the future.

The Role of Environmental Factors

Geography wrote the rules of early communication. Mountain dwellers developed long-distance signals - smoke puffs mirroring modern punctuation. Coastal tribes used wave-reflected flashes as primitive messaging. Each environment posed unique challenges that shaped local communication like wind shapes canyon walls. Understanding these adaptations reveals how deeply our surroundings influence how we connect.

The Emergence of Formal Sign Languages: From Oral Traditions to Codified Systems

The Genesis of Sign Language

Like rivers carving canyons, small signing communities gradually shaped complete languages. Isolated groups facing communication barriers didn't just invent signs - they developed grammars, syntax, and linguistic rules as complex as any spoken tongue. This organic growth proves language isn't about sound, but about the human need to connect and be understood.

As these systems matured, they absorbed cultural fingerprints. Just as accents vary by region, signing styles reflected local identities. Far from being universal, sign languages diversified beautifully, each version carrying the unique spirit of its community.

The Standardization and Recognition of Sign Languages

The battle for recognition transformed signing from gesture to respected language. Linguistic pioneers documented signs with the precision of dictionary makers, proving these weren't just improvised motions but structured systems. This academic validation opened doors, turning what was once seen as a disability accommodation into a celebrated cultural treasure.

Schools began treating sign language not as a last resort but as a first language. Deaf children could now learn in their natural mode of expression, their hands finally free to ask all the questions their minds could conceive.

The Impact of Formal Sign Language on Deaf Communities

With formal recognition came empowerment. Deaf individuals stopped being seen as broken hearing people and became recognized as members of a vibrant linguistic culture. Sign language became both a practical tool and a cultural banner, allowing deaf communities to celebrate their identity while fully participating in broader society.

This linguistic acceptance changed everything. Courts heard deaf testimonies, theaters offered signed performances, universities welcomed deaf scholars. The hands that were once forced to be silent now shaped laws, created art, and advanced science.

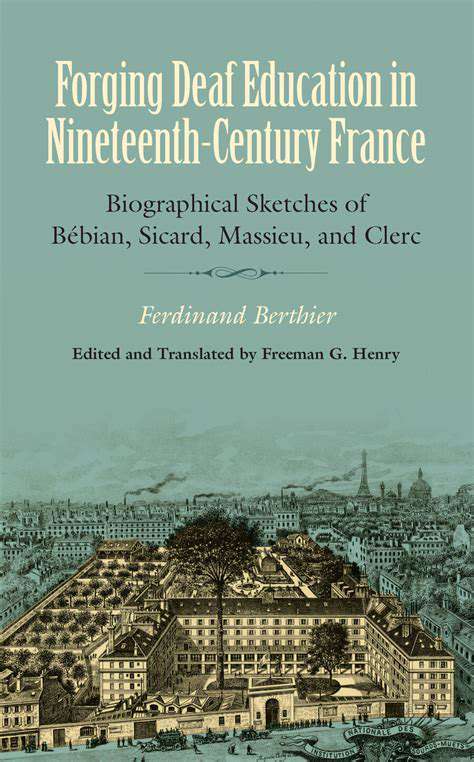

The 19th Century and the Rise of Deaf Education: A Complex Relationship with Oralism

The Industrial Revolution's Impact

As factories transformed landscapes, they also reshaped communication needs. The new industrial order demanded standardized education, including for deaf individuals who could contribute to the workforce. This practical need drove the creation of specialized schools, though often with conflicting philosophies about how deaf students should communicate.

Urbanization concentrated deaf populations, creating critical masses that could support dedicated institutions. Technological advancements in printing allowed educational materials to spread, though debates raged about whether to prioritize signing or speech.

Political and Social Upheaval

The century's democratic stirrings reached deaf education. As marginalized groups everywhere demanded rights, deaf advocates fought for educational autonomy. The choice between oralism and signing became more than pedagogical - it was political, about whether deaf culture had the right to exist on its own terms.

Cultural and Intellectual Developments

Romanticism's celebration of unique identities influenced some educators to value signing as a cultural treasure rather than a deficiency. Meanwhile, scientific breakthroughs in understanding language acquisition began challenging oralism's dominance, though change came slowly against entrenched prejudices.

Technological Advancements and Innovations

New inventions like the telephone ironically made the world more hearing-centric, increasing pressure on deaf individuals to conform. Yet these same technologies would later create tools for deaf accessibility, demonstrating how innovation cuts both ways for minority communities.

The Future of Sign Language: Adapting to a Changing World

The Evolution of Sign Language Technology

Digital tools are transforming signing from an intimate art to a globally connected practice. Translation apps don't just bridge languages - they're creating new hybrid forms of communication where signs can instantly become text or speech, breaking isolation barriers that persisted for centuries.

Accessibility and Inclusivity in Education

The classroom revolution goes beyond interpreters. Forward-thinking schools now treat sign language not as accommodation but as enrichment, offering it to hearing students as a window into neurological diversity. This shift recognizes that deafness isn't a deficit to overcome but a perspective to include.

Preserving Cultural Heritage and Linguistic Diversity

As globalization threatens small languages everywhere, sign languages face similar risks. Documenting regional signing variations becomes as crucial as saving endangered spoken tongues, preserving not just communication methods but entire worldviews encoded in gesture and expression.

The Role of Sign Language in Cross-Cultural Communication

In our interconnected world, signing offers unique advantages. Where spoken languages divide, the visual grammar of signing can create unexpected bridges, sometimes proving more universally understandable than verbal communication across cultural boundaries.

The Future of Sign Language Research and Development

Neuroscience is revealing how signing shapes brains differently than speech. These discoveries may revolutionize not just deaf education but our fundamental understanding of human cognition, proving that language is far more flexible and adaptable than previously imagined.

Read more about The History of Sign Language and Its Development

Hot Recommendations

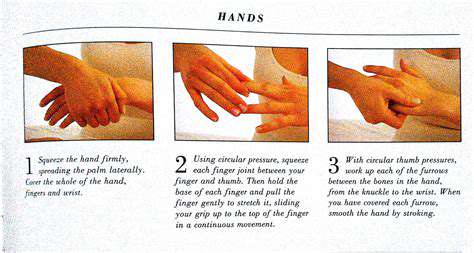

- The Impact of the Digital Age on Hand Function

- The Role of Hands in Agricultural Innovation

- The Impact of Technology on Hand Artistry

- The Importance of Hand Care for Artists

- How Hand Control Enhances Robotic Surgery

- The Impact of Hand Strength on Physical Labor

- How Handwriting Influences Cognitive Development

- The Impact of Environmental Factors on Hand Health

- The Power of Hands in Building Community

- The Importance of Ergonomics in Hand Health