The Role of Physical Therapy in Hand Recovery

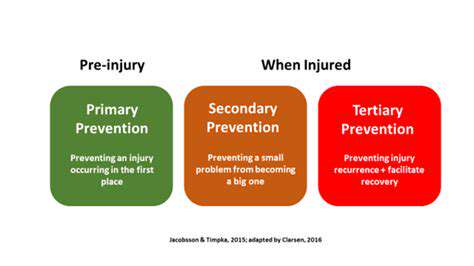

For example, a tendon cut needs different care than a broken finger bone. Accurate classification prevents wasted time on ineffective treatments and helps patients understand their recovery path.

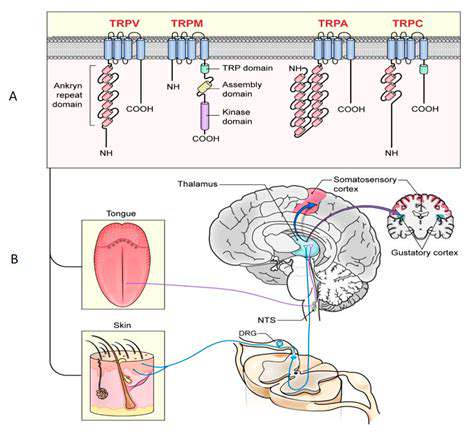

Checking Sensation Changes

When hands can't feel properly, everyday tasks become dangerous and difficult. Testing should check different sensations - light touch, sharp/dull feeling, temperature sense - across all finger areas. Mapping out any numb spots or unusual sensations helps target therapy to protect and potentially restore feeling.

Measuring Movement Ability

Muscle and tendon injuries show up as weakness or clumsiness. We use specific tests to measure grip power (like squeezing devices), pinch strength (thumb-to-finger), and fine coordination (buttoning shirts). These measurements create a baseline to track whether exercises are working.

For instance, someone who can't hold a coffee mug needs different exercises than someone struggling with writing. Regular strength checks show if the treatment plan needs adjustment.

Tracking Joint Movement

Stiff joints are common after hand injuries. We measure how far each finger joint bends and straightens, both when the patient moves it themselves and when we help. Thumb motion gets special attention since it's crucial for grasping. These precise measurements, taken weekly, show whether stretching exercises are effective.

Practical Function Assessment

The real test of recovery is whether the hand works when needed. Can the person open jars? Use keys? Wash dishes? We observe these real-world tasks rather than just office tests. For workers, we might simulate job demands like tool use. This practical focus ensures therapy translates to daily life rather than just improving clinic test scores.

Creating the Treatment Roadmap

After gathering all this information, we consider possible diagnoses and create a step-by-step plan. This might combine exercises, special braces, hands-on therapy, and education about protecting the healing hand. The best plans evolve as the injury heals, starting with protecting the area, then restoring movement, and finally rebuilding strength.

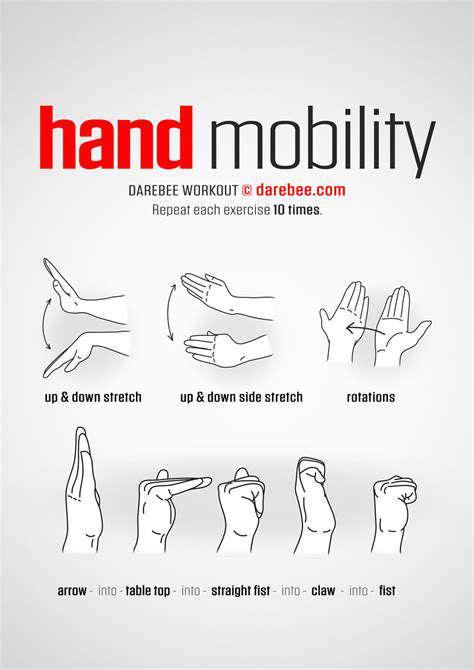

Restoring Mobility and Range of Motion

Joint Recovery Strategies

Regaining hand movement requires a gradual approach. Starting too aggressively can cause setbacks, while moving too slowly risks permanent stiffness. Early therapy focuses on gentle motions within comfortable limits, perhaps using heat to relax tissues. As healing progresses, we introduce more challenging movements and resistance.

Special tools like therapy putty or spring-loaded devices help rebuild strength safely. The key is consistency - short, frequent practice sessions work better than occasional intense workouts. Patients who stick to their home exercise programs see the best long-term results.

Practical Function Restoration

True recovery means using the hand normally again. We break down daily tasks into manageable steps - maybe starting with holding a toothbrush before attempting to squeeze toothpaste. Occupational therapists excel at finding creative solutions, like special grips for utensils or modified clothing fasteners during recovery.

Workers might practice with job-specific tools at lighter intensities. Musicians benefit from adapted practice routines. This tailored approach considers each person's unique goals rather than just generic exercises.

Improving Strength and Function

Foundation Building

Hand strength recovery begins with understanding how all the parts work together. The small hand muscles rely on proper wrist and forearm positioning. We often start by stabilizing these larger areas before focusing on finger movements. Simple exercises like wrist rolls or squeezing a soft ball build this foundation.

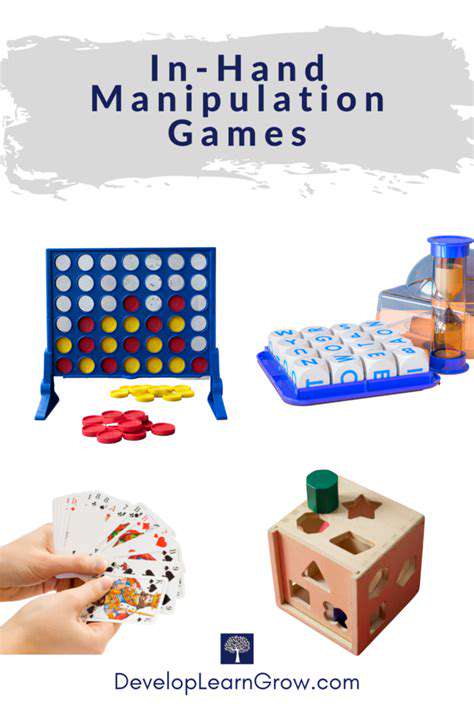

Progressive Challenges

As the hand heals, we systematically increase demands - perhaps moving from squeezing foam to therapy putty, then to spring grippers. The 10% rule works well - never increase difficulty more than 10% at a time to avoid reinjury. Detailed progress tracking helps find the right challenge level.

Activity-Specific Training

A mechanic needs different hand strength than a pianist. Final-stage therapy mimics real demands - turning wrenches for the mechanic, finger independence drills for the musician. This targeted approach bridges the gap between clinical recovery and real-world readiness.

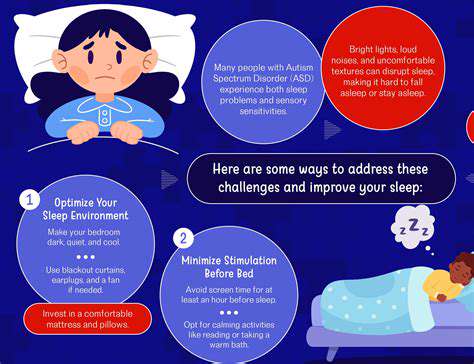

Addressing Pain Management and Sensory Recovery

Understanding Persistent Pain

Chronic hand pain often involves multiple factors - nerve sensitivity, tissue scarring, even fear of movement. Effective treatment addresses both physical and psychological aspects. Gentle desensitization techniques help with nerve pain, while graded activity rebuilds confidence in using the hand.

Sensory Retraining

For numbness or abnormal sensations, we use texture discrimination exercises - identifying objects by touch alone, or distinguishing between cotton and sandpaper. These methods can gradually retrain the nervous system to interpret sensations correctly again.

Holistic Approaches

Sometimes pain persists despite tissue healing. In these cases, techniques like mindfulness can help break the pain-stress cycle. Teaching patients about pain science often reduces fear and improves outcomes more than any single treatment.