The Evolution of Handwriting: From Quill to Keyboard

Catalog

- Early communication relying on symbol systems

- Innovation in reading and writing methods by Chinese papermaking

- The quill pen enhances writing precision in the sixth century

- The printing press promotes the democratization of knowledge

- Modern writing instruments enhance writing convenience

- Digital communication rewrites the rules of writing

- The new positioning of handwriting in education

- Artists rediscover traditional writing tools

- Printing technology shapes language standardization

- The typewriter changes the writing ecosystem

- Revival of vintage typewriter culture

- The evolution of input methods in the digital age

- Trends in the integration of future writing technologies

The Dawn of Written Communication

The Birth of Primitive Writing Forms

On the clay tablets of the Mesopotamian plains, ancient scribes used reeds to imprint cuneiform symbols, a scene that feels vividly close. These tablets not only recorded lists of goods but also witnessed humanity's first attempt to convert spoken language into permanent symbols, a groundbreaking moment.

As pictographs gradually evolved into ideograms, the entire society's way of transmitting knowledge underwent a fundamental change. Trade caravans carried clay tablets inscribed with symbols across the desert, establishing an unprecedented information network between city-states, a shift that directly birthed the earliest archival management systems.

The Civilizational Leap Triggered by Papermaking

Eastern Han eunuch Cai Lun probably never imagined that the sheets made from tree bark and rags would completely change the course of civilization. This lightweight writing medium allowed the dissemination of knowledge to break free from the constraints of bamboo slips, enabling scholars to easily carry scrolls of texts, a convenience that directly propelled the formation of the imperial examination system.

The caravans traveling westward along the Silk Road not only transported silk but also carried Eastern secrets that would transform Western civilization. When the papermaking workshops in Damascus began to emit smoke, the scribes of parchment along the Mediterranean coast were still unaware that they were about to be rendered obsolete by history.

The Golden Age of the Quill Pen

Under the candlelight of monasteries, monks held carefully trimmed goose quills, sketching elegant Carolingian minuscule on parchment. This tool, which required dipping into ink after every ten letters, unexpectedly nurtured a habit of deep thinking among medieval intellectuals—the frequent pauses for dipping allowed time to organize logical language.

The famous scribe Alcuin once complained in his diary: \Today, I broke three fine swan quills, and the ink has stained the Book of Psalms again.\ These daily grievances led to the invention of metal pen tips, laying the groundwork for modern writing instruments.

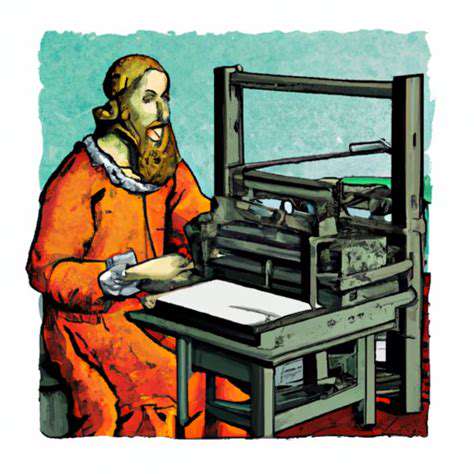

The Chain Reaction of Moveable Type Printing

In the workshop of Mainz goldsmith Gutenberg, neatly arranged lead type modules awaited inking. When the first mechanically printed Bible was published, the era of the church monopolizing knowledge entered its countdown. This technology reduced the time required to produce a single book from months to days, allowing the speed of knowledge dissemination to exceed the limitations of oral transmission for the first time.

Interestingly, early printers often reused woodblock prints to save costs, which resulted in the same decorative patterns appearing in different books. This phenomenon of template reuse inadvertently contributed to the stylistic unification of European decorative arts.

The Writing Revolution in the Digital Age

The Cognitive Reconstruction of Keyboard Input

When the first commercial typewriter rolled off the assembly line at Remington, no one anticipated that the QWERTY layout would last for a century. This arrangement, designed to reduce mechanical failures, unexpectedly shaped the muscle memory of modern individuals. Neuroscientific research shows that professional typists develop special connection patterns between the brain's language and motor areas.

The Paradox of Writing in the Touchscreen Era

Smart devices have made text input unprecedentedly convenient, yet research from the University of California found: students taking notes on tablets have a 40% lower content retention rate than those writing by hand. This difference gave rise to smart notebooks that combine the experience of paper and pen, digitizing handwritten content through special paper, cleverly balancing tradition and technology.

Outlook for Future Writing Forms

The neural interface pen being developed at ETH Zurich can recognize writing intentions through electromyographic signals. Designer Yohji Yamamoto from Tokyo has launched scented ink that lends a unique aroma to each letter. These innovations suggest to us that the revolution in writing tools is far from over; it is entering a wondrous interaction with biotechnology and materials science.

In a handmade pen workshop in Munich, a master craftsman said while polishing a tortoiseshell pen barrel: True writing should allow one to feel the rhythm of the ink flowing. This emphasis on tactile sensation may just be the missing key dimension in human-computer interaction design.

Read more about The Evolution of Handwriting: From Quill to Keyboard

Hot Recommendations

- The Importance of Hand Care in Scientific Professions

- Exercises to Enhance Balance and Prevent Falls

- The Impact of High Heels on Foot Structure

- Preventing Foot Blisters During Long Walks

- Managing Plantar Fasciitis: Tips and Strategies

- Preventing Foot Injuries in Athletes

- The Benefits of Yoga for Foot Flexibility

- The Relationship Between Obesity and Foot Problems

- The Impact of Flat Feet on Overall Posture

- Addressing Bunions: Causes and Treatment Options